History is everywhere. In our work, in our going to and fro, in our families, in our nature. It is in our nature that we find time to gather and save and in doing so, we preserve our history. Newspaper clippings, photos, dried flowers from a bouquet, recordings of all manner, even antique buying. It’s innate to us as people to hang on to what once was. Our reasons are as many as the items themselves, but I hunt these histories as a hobby. I mine the leftover media from attics and closets and occasionally I strike gold.

By remarkable coincidence, a recent find in a single old black paper bound photo album in my collection has brought me fragments of the history that I seek; these previously unknown to me moments in time. Here are three of the most terrible disasters in U.S. Navy history from peacetime in the early part of the past century, just over 100 years ago. One I knew about. Two I had never heard of. All occurred within just 2 years and 17 days in the middle part of the 1920s and spanned the country from one sea shore to the other. One album, 3 disasters, forty lives lost.

On the Rocks

On September 8, 1923 14 Clemson-class US Navy destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 11 left San Francisco Bay for an exercise down the California coast. The goals along the way were many, including a passage through the San Barbara Channel just off the California coast. This would have been easy with good conditions, but the weather had worsened to the point of heavy fog and low visibility. Navigation at the time was still relying mostly on dead reckoning as radio navigation aids were new and generally not thought of as accurate enough to trust. The overall commander of the force, Captain Edward H. Watson ordered the ships to close up and follow in column. Then following the recommendations of his lead navigator he ordered the turn to the east to enter what he thought would be the Santa Barbara Channel. Instead, the first seven ships of the column steamed directly into the rocky outcrops known to 16th century Spanish explorers as The Devil’s Jaw.

Watson’s flagship USS Delphy hit first at 20 knots. The USS S.P. Lee turned to avoid the Delphy and crashed into the shoreline bluffs. The USS Young made no apparent attempt to alter course and plowed directly over several submerged rocks ripping the hull open. She flooded and capsized to starboard immediately. USS Woodbury turned to avoid the others and grounded on more rocks. USS Nicholas also turned the other way to avoid the developing disaster ahead and ran over a rock. USS Fuller struck rocks next to Woodbury. Finally, USS Chauncey ran aground trying to come to the aid of the capsized Young. 3 men aboard Delphy were killed, while 20 lost their lives in the flooded engineering spaces of the Young.

USS Farragut and USS Somers followed next, but due to warning horns and signals they had slowed enough to avoid crashing into rocks, running aground but without damage. Each was able to back off and stay afloat clear of the mess. All of the remaining ships of DesRon 11 stayed off and immediately began launching boats to aid in the rescue of the stranded crews. Rescue was not completed by ship’s boats and shore based efforts until the next day. The Navy made no attempt to salvage any of the seven destroyers, instead selling them where they were for scrap.

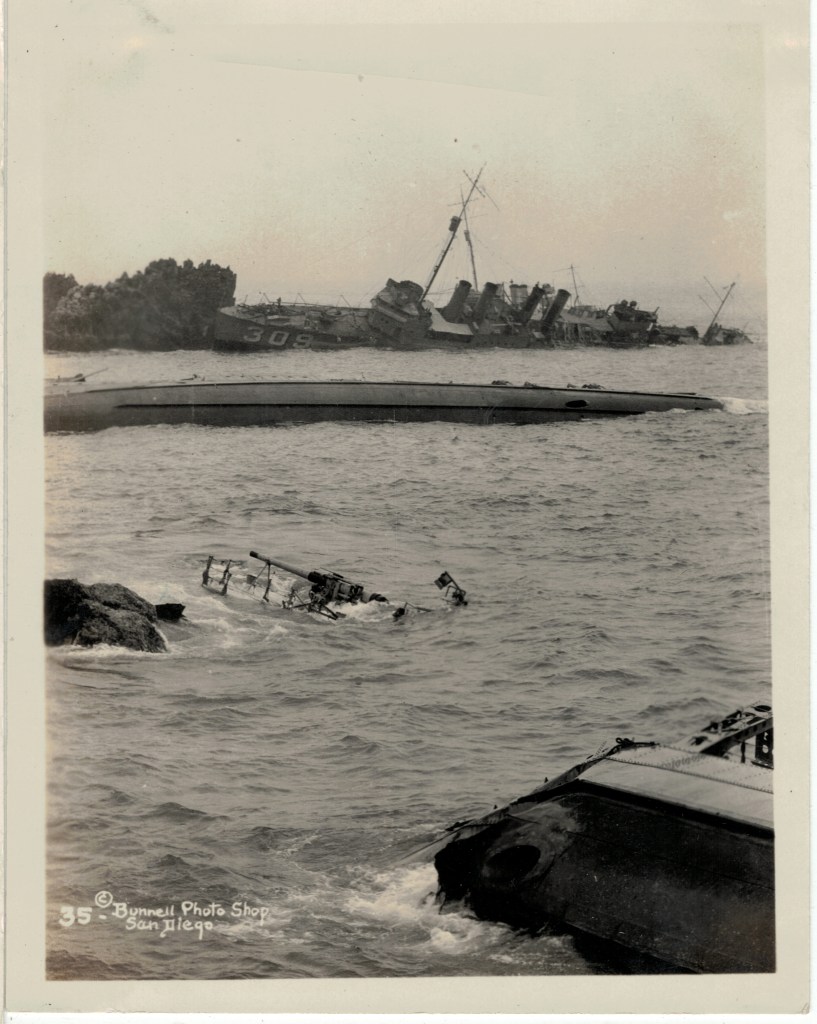

Chauncey in the foreground, then capsized Young, with Woodbury and Fuller (fartherest) on what would become known as Destroyer Rock.

USS Nicholas along with one of the rescue boats.

S.P. Lee left, Nicholas center.

Delphy now over on its starboard side in the foreground, Capsized Young, Woodbury and Fuller on Destroyer Rock.

USS Chauncey grounded, Young’s hull behind, Woodbury to the left.

USS S.P. Lee up against the bluffs. Woodbury and Fuller in the background.

USS S.P. Lee from the stern with some of the crew still aboard. Illustrates the weather and the subsequent pounding the destroyers took while on the rocks.

USS Delphy now lies broken in half with the stern submerged. Aft gun barely above water.

S.P. Lee foreground with Nicholas. Both ships being battered by the weather. Later photos show Nickolas’ entire bow detached to starboard.

One final note. One week prior to the disaster at Honda Point and the rocks at The Devil’s Jaw, the Great Kanto earthquake in Japan occurred, doing a massive amount of damage to Tokyo and Yokahama. The 7.9 earthquake is believed to have affected Pacific ocean currents a great deal and may have had a part in ruining the navigation efforts of DesRon 11 on the 8th, creating chaos on the California shoreline and along the Santa Barbara Channel. Honda Point (or Point Pedernales today) is very close to Vandenberg AFB today.

In The Sky

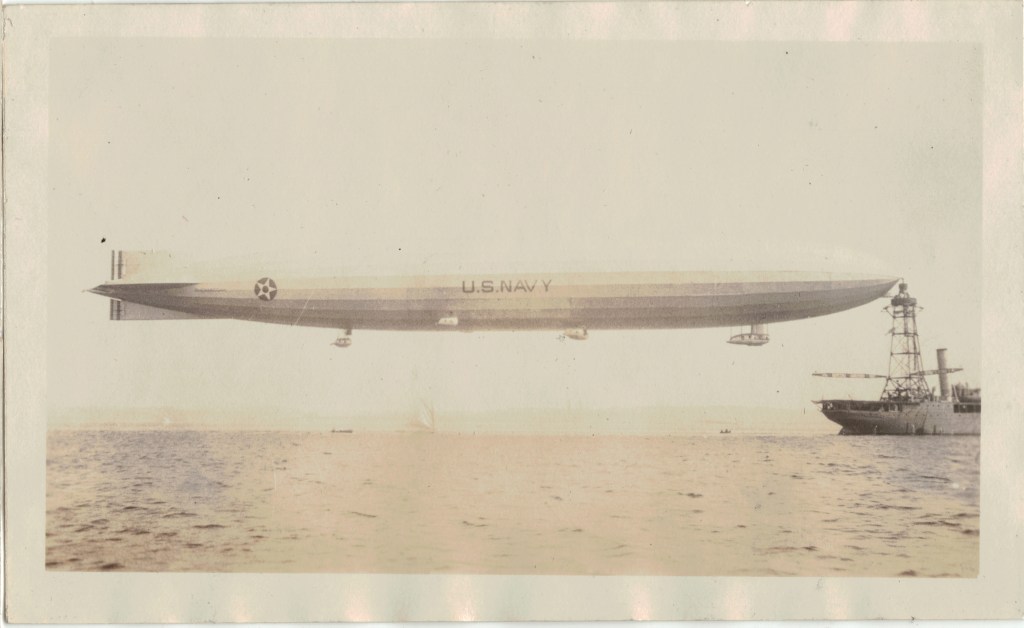

The USS Shenandoah did not sail the waves of the Seven Seas, but rather the waves of the air above. The first of four rigid airships operated by the U.S. Navy, she made her first official flight September 4, 1923. Four days before Honda Point. The airship pioneer the use of much safer helium rather than the common use of flammable hydrogen. The 36 ton, 680ft long beast could move at up to 70 mph or cruise at lower speed for 5,000 miles. She was built up at Lakehurst, New Jersey of parts fabricated at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia.

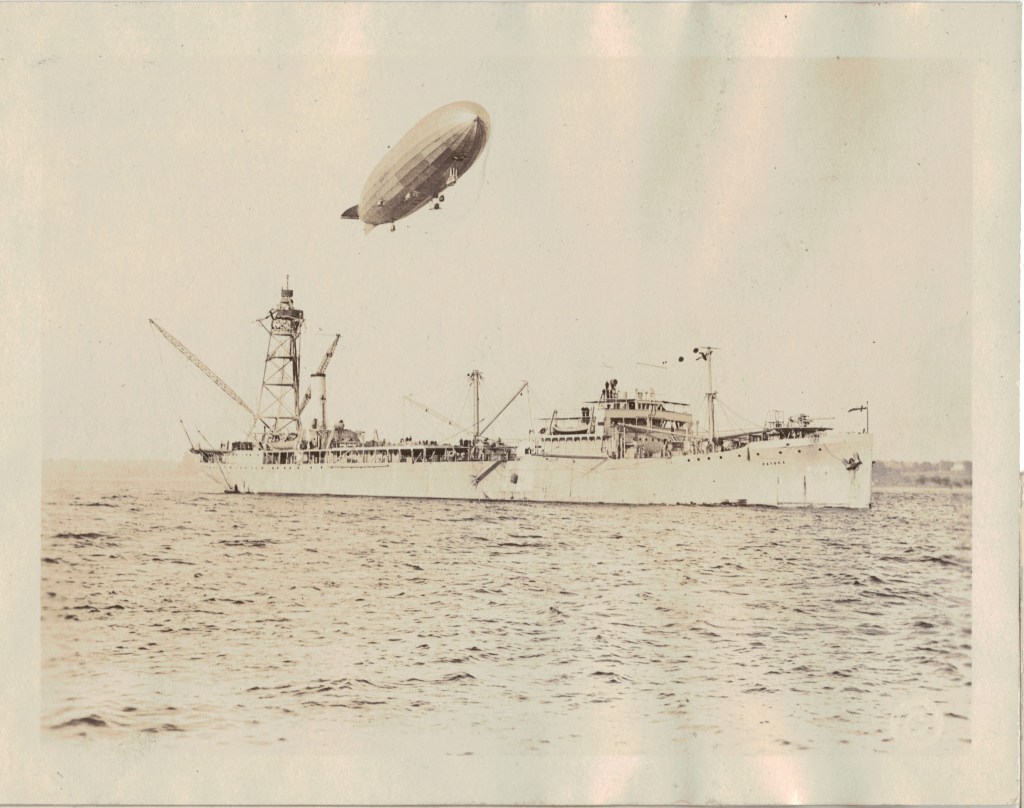

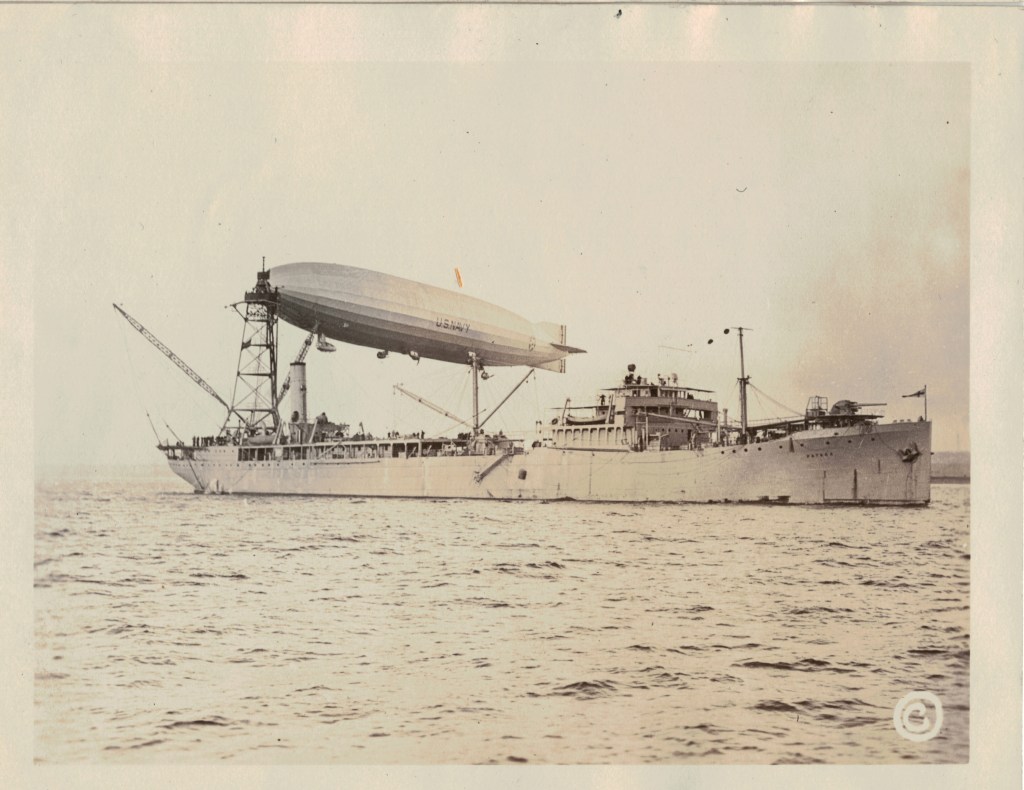

Designed to be operated much as the German airships of WWI were with a scouting and reconnaissance mission, Shenandoah would have had a crew of around 25 and would have spent its time in service scouting for enemy surface fleets. Exercises along these lines occurred in the summer of 1924 which served to point out that there was a shortfall in performance related to the limited amount of servicing available to an airship on active duty. As such, the oiler USS Patoka was modified with a mooring mast and additional servicing facilities to act as a mobile platform for airships on patrol offshore. Tests in August 1924 worked, and the airship departed in October for a round trip across the country to test new mooring sites in California and Washington. More scouting work occurred in the summer of 1925 along with the Patoka.

On September 2, 1925 USS Shenandoah departed on a cross country tour which was mostly a public tour event on the Navy’s behalf to justify to the public the huge expense of such an airship. On September 3rd she ran into a squall line near Caldwell, Ohio that proved too much for the lighter than air craft. Ripped apart into three sections which crashed separately over a six mile area. 14 crew members were killed in the breakup, leaving 29 survivors who rode the three sections until they crashed. This is the one story from the photo album that I already knew. There are no crash photos in the book, only three photos of the Shenandoah operating with the USS Patoka support ship.

When I realized this was the Sheneandoah it clicked that it was another naval disaster tied in to the photo album even thought it wasn’t a first hand record. To me it counted. I didn’t realize that there was a third in the last pages.

Under the Seas

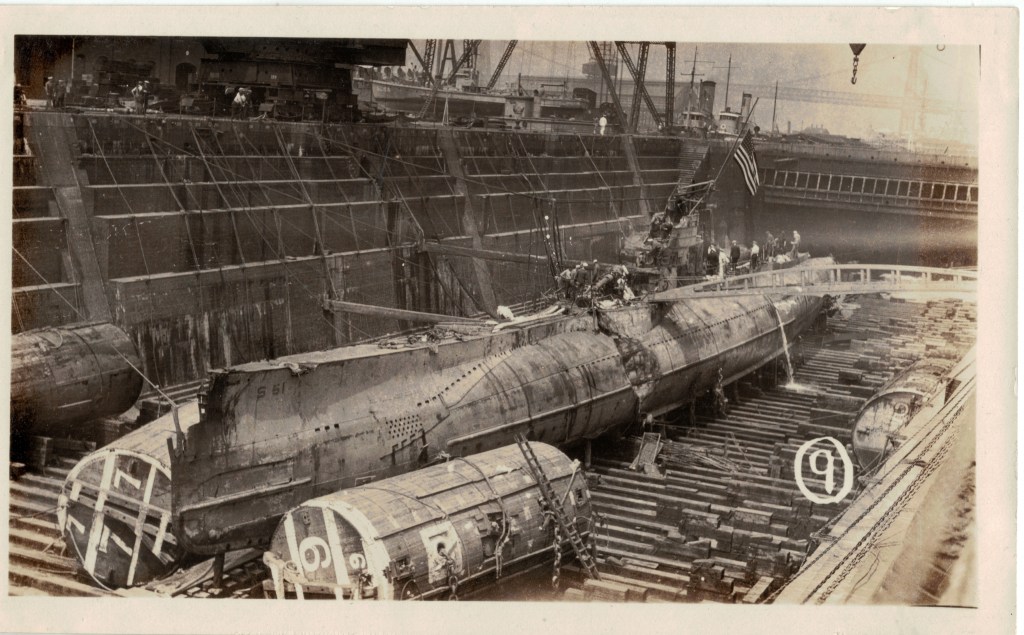

The United States submarine S-51 was launched at Bridgeport, Connecticut on August 20, 1921. She split her operational time between local training duties in the New England area from 1922 to January 1924, then further abroad in the Panama Canal Zone and Caribbean Sea during 1924. Back in the waters off Long Island, Connecticut, and Rhode Island more training in the coastal area occurred until September of 1925.

On the night of September 25, 1925 S-51 was running on the surface near Block Island with running lights on. The merchant steamer City of Rome was also in the same area and saw a single white masthead light. In the confusion that followed, one decision led to another and City of Rome rammed S-51 at 10:23pm. Of the 36 crewmen aboard S-51, only three managed to abandon ship. They were picked up by City of Rome but each was not on watch and had no further information to add to the circumstances of the collision. 33 crewmen died.

Several hours after the sinking, the wreck site was located by oil slick on the surface. When it had been determined that further rescue operations were futile, the salvage operation began on October 10th. The salvage operation itself is an epic story and lasted until July 8, 1926 when the vessel, suspended under flotation pontoons, arrived at the New York Navy Yard. The journey was slow and the sub even briefly ran aground on Man-O-War Reef in the East River. The following photos show the salvage tow and the extensive damage to the sub revealed in dry dock.

Ocean tugs Iuka and Sagamore begin towing the refloated S-51 and pontoons. USS Vestal leading in the distance.

Impact point of City of Rome on the port side.

Damage to stern.

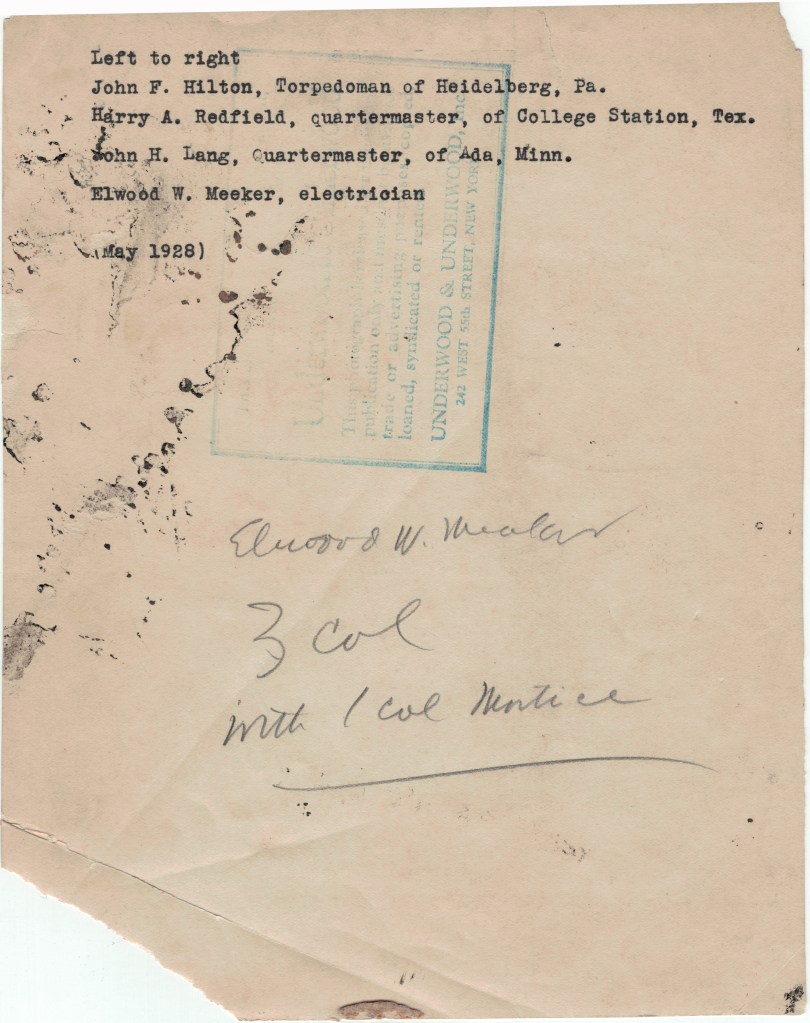

I believe all of the photos I have used for this posting are copies of originals, and that they are more than likely all in the public domain or fair use category. They all came to me in the form of an antique photo album that belonged to a man named Elwood Wallace Meaker. There are photos in the book that I’m sure Elwood took himself, but none are related to the stories above. In fact, it is Elwood’s own story that I would like to know more about. I don’t know if he had any personal connection to the disastrous events event of the 20s found in his album, or if they just interested him enough to be collected and saved for another day. It could go either way. Elwood was a Navy man. He was an electrician and as indicated, served aboard the destroyer DD-237, the USS McFarland; a Clemsen-class destroyer. The same as Destroyer Squadron 11 that dashed itself upon the rocks off California. The album is a story in itself and Elwood is part of it. What part, I must say I do not know. Everyone has a story. A story worth telling. Perhaps Seaman Meaker’s will find the light of day. Someday.

Oddities

All three Naval disasters occurred in the 1920s. Not terribly odd on its own, but two more submarines sank in the 1920s; S-5 in 1920 and S-4 in 1927. All hands were saved from S-5. All of these disasters occurred in the month of September except S-4 in December. Destroyer DD-237 USS McFarland on which Elwood Meaker served was rammed by the battleship USS Arkansas. In September, 1923. It was towed for repairs and served in WWII.

Crewman Frederick J. Tobin survived the crash of the USS Shenandoah in 1925. In 1937 he was commanding a Navy Landing party for the arrival of German zeppelin Hindenburg in Lakehurst, New Jersey and helped rescue survivors of that airship when it burst into flames and crashed.

The salvage operation that raised the sunken submarine S-51 was commanded overall by then Captain Ernest J King. The USS Vestal repair ship was there participating in the effort. Ten days after arguably the worst disaster in Navy History December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, King replaced Admiral Kimmel as Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. The Vestal was there at Pearl Harbor being repaired herself after being hit by two bombs. She survived the war.

Modeling

For any of the DesRon 11 destroyers involved in the disaster on the rocks at Honda Point, your choice is a single model kit from Mirage Hobby in 1/400 scale. Boxed as the USS Noa it would build into any of the Clemsen-class destroyers. There are decal sheets out there that would give you the correct, or near correct sized drop shadow numerals for the needed hull numbers.

I do not know of a model kit for the USS Shenandoah. I have seen scratch built models at contests, but nothing is out there commercially.

There used to be a resin kit from Yankee Modelworks of an S class US submarine. However it is long out of production and is overall too short to represent the extended length of the last four subs of the S class including S-51.

References

Wikipedia for Honda Point, USS Shenandoah, and S-51

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1927/february/salvaging-u-s-s-s-51

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2020/october/disaster-honda-point